THUNDER BAY -- A pamphlet under glass on the wall of the Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service headquarters entrance reads, “NAPS officers do more.”

That may be so but if they do, they do it for less. Their leadership says that goes beyond dollars and cents.

NAPS’ collective bargaining conflict ended in July when an arbitrator ruled in favour of the officers’ PSAC Local 401, increasing pay by 11.8 per cent. That would bring a NAPS first class constable’s salary to $86,905, while their OPP counterparts clear $90,000.

The First Nations police service estimated its 2016 budget faced a $1-million deficit. NAPS Chief Terry Armstrong cut his projection to falling $850,000 in the red by April. But to break even without eating into operating expenses, he feels he’d have to lay off 20 officers.

Doing NAPS’ job right, he says, needs 52 more officers than its current complement of 147.

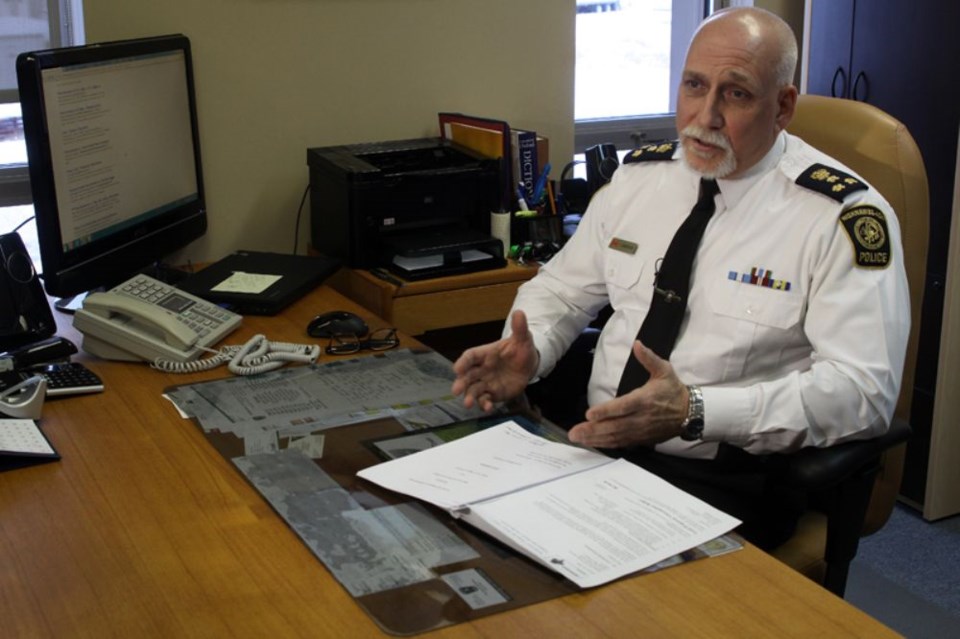

At the top of the stairs, Armstrong occupies the office at the end of the hall. That’s where he was on Jan. 5 when he received the federal government’s letter informing him it had rejected his July request for $3.45-million to meet the new labour contract.

If NAPS was a police service like most others, it could appeal to the Ontario Civilian Police Commission to balance government funding with public safety. But like all First Nations police forces, it was created as a program rather than a service.

Over its 21 years, Armstrong says NAPS has outgrown that definition.

Over its 21 years, Armstrong says NAPS has outgrown that definition.

“The program is considered an enhancement but we’re not enhancing anything anymore,” he says.

“We’re autonomous, other than major crime. We’re funded to enhance the OPP but we’ve moved the yardstick from what was intended as an enhancement to a full-fledged police force -- but we’re not funded as a full-fledged police force.”

Moreover, Armstrong argues the OPP is not structured to respond to immediate need when NAPS calls for assistance. Unlike the road-connected communities in Treaty Three, where Armstrong served as deputy chief, NAPS polices 23 fly-in communities.

“I can’t call up the (OPP) regional commander and say our officer in Fort Severn called in sick tonight. They won’t go up there without at least two guys and it will take them days to organize it. By then, we’ll have our next guy up there. We don’t have the same benefits that even other First Nations police services in the province have.”

The OPP polices four Nishnawbe-Aski Nation communities exclusively. It stations 17 officers in Kichenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation and the Pikangikum First Nation OPP detachment deploys 37.

Comparatively, NAPS supports Kashechewan First Nation with a force of seven, a disparity of five times as many civilians to officers.

Two inmates died in 2006 when a blaze tore through NAPS’ Kashechewan station. Amid 80 recommendations, an inquiry into the deaths of inmates Jamie Goodwin and Ricardo Wesley condemned non-existent standards for jail cells and police infrastructure on First Nations.

That finding was echoed in the 2014 Auditor General’s Report, which found “no reasonable assurance that policing facilities in First Nations communities are adequate.”

The Auditor General pointed out half of First Nations policing services surveyed had replaced provincial core services while Public Safety Canada had no definition for “enhanced” policing services in First Nations.

Political solutions sought

The Nishnawbe-Aski Nation Chiefs Assembly passed a resolution last year to lobby for NAPS to be brought under the Ontario Police Services Act, which would change its status to an essential service.

NAN Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler is handling the file personally.

NAN Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler is handling the file personally.

“We’re working as hard as we can to address those conditions, not only for our communities but to give assurance to our officers out in the field that we’re aware of the conditions they’re working in right now and that we’re working hard to change those conditions to make things better for them so they’re able to do their work,” Fiddler says.

Ontario’s Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services is developing the Strategy for a Safer Ontario, the province’s biggest transformation to the Police Services Act in a quarter-century.

While a ministry spokeswoman wouldn’t say whether it intends to bring First Nations policing under the Police Services Act, Courtney Battistone issued a statement confirming consultations on the future of First Nations policing are underway.

The federal government contributes 52 per cent of NAPS’ funding. MP Don Rusnak (Lib., Thunder Bay-Rainy River) is committed to bringing the issue before his party's Indigenous Caucus.

“They don’t have a source of stable funding because they’re just a program,” Rusnak says.

“It’s something that has got to be addressed. We’ll have to work in consultation with our provincial partners and our First Nations partners to make sure their communities have equal policing to non-First Nations communities -- that they get the same dollars for protecting their communities.”