There are currently 568 Aboriginal children in foster care throughout the district.

Donald Auger says the number of children in care has doubled in the six years since he became executive director of Dilico Anishnabek Family Care, a multi-service agency that also provides child welfare services for the district’s Aboriginal population.

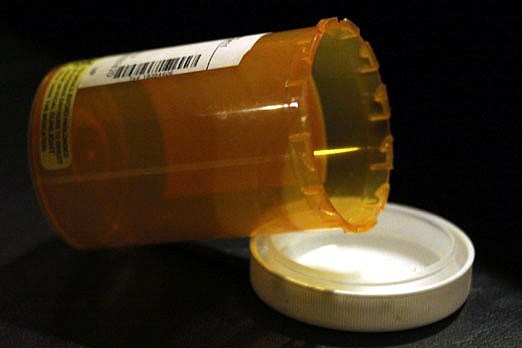

In up to 80 per cent of the cases, the child enters care because of neglect due to drug use by the parent.

“This has gotten to become an epidemic,” Auger says. “Drugs are a huge, huge problem.”

In some cases, 25 per cent of an adult population is addicted to prescription drugs, Auger says.

Auger cautions that the drug problems faced by the Aboriginal community are no different than any other population and that the same problems are happening everywhere.

“There are no boundaries with addiction. Everybody has the same problem.

“This causes a ripple effect on every social service agency in the area.”

For a child to be taken into service, they have to be deemed at risk. Dilico director of child welfare services Susan Verrill says only a quarter of the children served by Dilico end up in care.

“We work with a lot of kids that are deemed in need of protection but they still remain at home.”

The result is that Dilico is growing every year to keep up with service demands.

“What it means for us is that we’re always trying to catch up and have enough staff to provide the service to the children that we need and want to provide to them,” she says.

Physical and sexual abuse only account for around 14 per cent of cases where children are taken away.

And while those types of cases have lasting effects on a child, problems from neglect are worse, Verrill says.

“The effects can be far more devastating for a child who is suffering neglect,” she said.

Ther is also the problem of lasting effects from parental drug use. Verrill said methadone, a treatment to get users off of drugs like Oxycontin.

“What we’re seeing now are babies born addicted and they’re born addicted to methadone and their recovery, their withdrawal is far more serious, it’s far more difficult on the infant than recovery from cocaine or another drug,” she says.

Auger worries about the lasting effects on drug use similar to alcohol use by parents on children.

“Twenty years from now maybe even less than that we’re going to start seeing the effects in the children,” he said.

The effects on going through care can also be long lasting. While just less than 50 per cent of foster homes are Aboriginal, children are often going into strangers homes, away from their communities. This can lead to separation issues.

“I think it’s fairly traumatic for children because they’re leaving their home, they’re leaving the people that they know and rely on to care for them,” Verrill says.

And in up to 40 per cent of cases, the children are repeat cases, which means they come to learn and rely on the system. Some children will race upstairs and pack their bag when a case worker comes to the door because they know they are treated much better in a foster home.

“What’s very sad is that they’re very happy to come into care,” Verrill says.

There’s also a loss of culture if a child is placed in a non-aboriginal home out of their community. Auger, who is Ojibwa, said although he is well-educated in a Western system he will never know everything about his culture because he doesn’t speak the language.

“They lose their home but they also lose their culture.”

For those reasons, Dilico tries to place children with relatives whenever possible, which is called kinship care.

But it’s also getting the communities involved in customary care so a child can be placed with anyone they know in the community. Working closely with the community’s band, Auger said the future of Dilico’s role in child welfare will be to find homes for children so they can live where they know.

“Communities have a responsibility to look after they’re children, to look after their band members,” Auger says.

“I think communities can do a far better job because they know the family they know the relatives they know lots of stuff that we don’t know.”

That concept is as old as the communities themselves, but Auger said the problem is sometimes a 12,000 year-old system and the 60-year-old Ontario Child and Family Services act at odds.

“It just doesn’t work very well,” he says.

An example of that is the fact that community members or relatives who offer to take a child in aren’t compensated the way foster families are, Instead, they receive $135 a month through Ontario Works.

“Kids cost more than that,” Verrill said.

“Many of our parents don’t have the finances to support another child.”

Follow Jamie Smith on Twiter @jsmithreporting