The concrete jokes were flying fast and furious on Friday, but behind the laughter was encouraging news for Lakehead University researchers, construction companies and quite possibly even the planet itself.

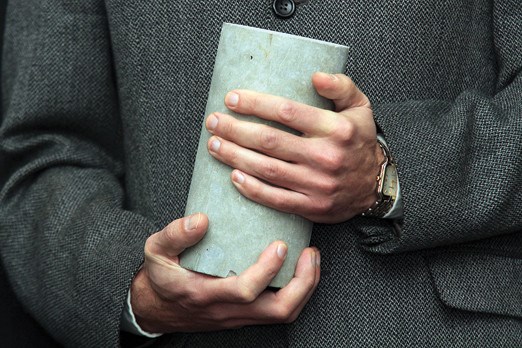

Using pulp and paper waste or fermented biomass, a pair of university professors unveiled a chemical additive that when added to the concrete recipe has the potential to vastly reduce the carbon footprint by lessening the amount of cement needed, while at the same time strengthening the concrete mixture by up to 50 per cent.

It will also significantly lower the cost.

The saccharide-based additive, which has been licensed in partnership with GreenCentre Canada, should also help lower the cost of concrete, said chemical engineering professor Lionel Catalan.

The discovery comes at a crucial time, he added.

With the demand for concrete on the rise, especially in developing countries like China and Eastern Europe, and expected to reach 40 billion tonnes worldwide by 2015, Catalan said the additive could have a global impact.

"The cement in concrete represents most of the carbon footprint of when you make buildings. By using our additive it can decrease the amount of cement in concrete by up to 50 per cent," Catalan said. "This would have huge repercussions on the amount of carbon dioxide that is emitted worldwide."

According to research partner Stephen Kinrade, a chemistry professor at the university, the production of one tonne of cement releases about one tonne of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

That’s second only to transportation in the creation of greenhouse gases, he said.

"That’s seven to 10 per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions," Kinrade said.

The manufacture of Portland cement involves heating calcium carbonate and clay at very high temperatures. Presently 1.35 billion tonnes are created each year.

"You can see the huge effect that implementing this technology would have. What’s also interesting for the region is the additive that we’re using in order to bring this increased strength and lower amount of cement in concrete is partly derived from the pulp and paper industry," Catalan said. "So there are certainly opportunities locally for economic development and maybe create jobs as well because of this discovery."

Kinrade said the additive was discovered almost accidentally, as he and his students were experimenting with silicon diluted in water.

"We discovered that certain sugar derivatives gave some very unique chemistry that people hadn’t recognized before. This has taken us into many areas. We saw an application in this, we approached Dr. Catalan, because he’s an expert in concrete and cement, so it’s with him that we’ve taken our research in that direction," Kinrade said.

For LU president Brian Stevenson, the possibilities are endless. Marketed by the university’s innovation management office, it’s the start of what Stevenson hopes are more partnerships and licensing opportunities to come.

"This is a product that is going to have relevance in the world. It’s environmentally friendly. I think what the community has to see is the inventiveness and creativity that a research-intense and comprehensive university can bring," Stevenson said. "It’s very important because we could just be an undergraduate university, just teaching. But our ambitions are greater. We want to have graduate programs, we want to be able to have research. This is the result of that kind of mix."

GreenCentre Canada and the scientists continue to work together to improve the product, said the company’s executive director Rui Mesendes.