THUNDER BAY -- If Southern Ontario is "the new rustbelt," Northern Ontario's labour market is even rustier.

The Economist magazine coined the term in last week's issue, comparing the collapse of Southern Ontario's manufacturing industry to that of the American Midwest a decade ago.

It suggests unless investements are made in value-added production, Ontario's manufacturing future is bleak.

Lakehead University economics professor Livio Di Matteo agrees lost manufacturing in the south is as unlikely to return as the pulp and paper industry is in the north. The new "advanced manufacturing" that is emerging, he points out, is technologically-intensive but not labour-intensive.

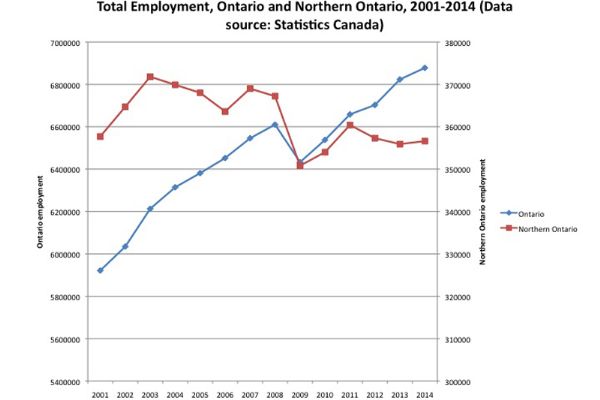

But while the provincial labour markets have rebounded from the 2008-2009 recession, his data shows Southern Ontarians have found new jobs where Northerners have not.

"There has been growth in other sectors of the economy -- services, transportation,tourism, retail -- that have created jobs that are replacing those lost in its declining sectors. In Northern Ontario however, total employment has declined in the wake of its manufacturing decline," Di Matteo says.

"Moreover, much of the decline in Northern Ontario was actually fueled by the Northwest where employment went from a peak of 117,000 in 2003 to 99,800 in 2014."

Di Matteo doesn't expect resource development to rebound until commodity prices begin to recover and even when that happens, he says similarly advanced technology in the mining sector will mean fewer jobs will be created.

Despite those figures, the North Superior Workforce Planning Board is observing population growth and in-migration throughout Northwestern Ontario.

"The North is far from over," says planning board executive director Madge Richardson.

"We need to continue to encourage people to move here to sustain our economy and keep building upon it... There are jobs, there are job vacancies and that's going to continue because because we're an aging workforce. There's going to be enough jobs for all the Aboriginal population and we're going to need a whole lot of people moving in from outside the province as well."

Consultations are underway to collect new employment market data that will be released later in the fall. Richardson says the Northern Growth Plan was designed to foresee and respond to fluctuations in labour markets but the province either isn't following through on those commitments or it isn't making its findings public.

"They had some wonderful indicators within that plan," she says.

"Workforce development was a very important aspect as it is in any economy because they're not going to have any economic activity without the people. We're not going to be able to sustain an economy without people having a wide range of skills and capabilities to be active in that economy.

"If they're making strides within that plan, they're not communicating them."

Sonja Waino is Richardson's equivalent in the Northwest Training and Adjustment Board. With Alberta's oil boom cooling off, she sees more skilled workers returning home to the region but doesn't think they will be enough to satisfy the appetite for business growth that has already begun.

"I think it's coming but it isn't showing up in the numbers yet because it's in the process of happening. What I see as the biggest problem is, we don't have a labour force," she says.

"For too many years, we didn't encourage our youth to go into blue collar jobs, which are well-paying. We wanted all our kids in university. We have a lot of young graduates but they don't have jobs that suit what they took.

"That's where we've been focusing our efforts is to change that theme of thinking because we need our middle class back."