THUNDER BAY — Students at Confederation College have created a project quantifying just how much of Thunder Bay’s waterfront is available for public access.

Madison Dyck and Matthew Greenberg, both students in the college’s forestry program, say their shoreline mapping project is intended to spark conversations about residents’ relationship with Lake Superior.

The GIS mapping project was inspired after Dyck’s personal goal of swimming in the lake each week drove home the relatively small number of places where it’s safe and possible to do so around the city.

Thanks to the city’s industrial history, that’s often dependent on having a car and some disposable income, she said.

“I’m from Thunder Bay, I love the lake,” she said. “For years, I’ve always been trying to find new places to get on the lake and explore, and I feel like I’ve exhausted all of them. In my head, I’d think about it and talk to people, but I’d never laid it out, like what does this actually look like?”

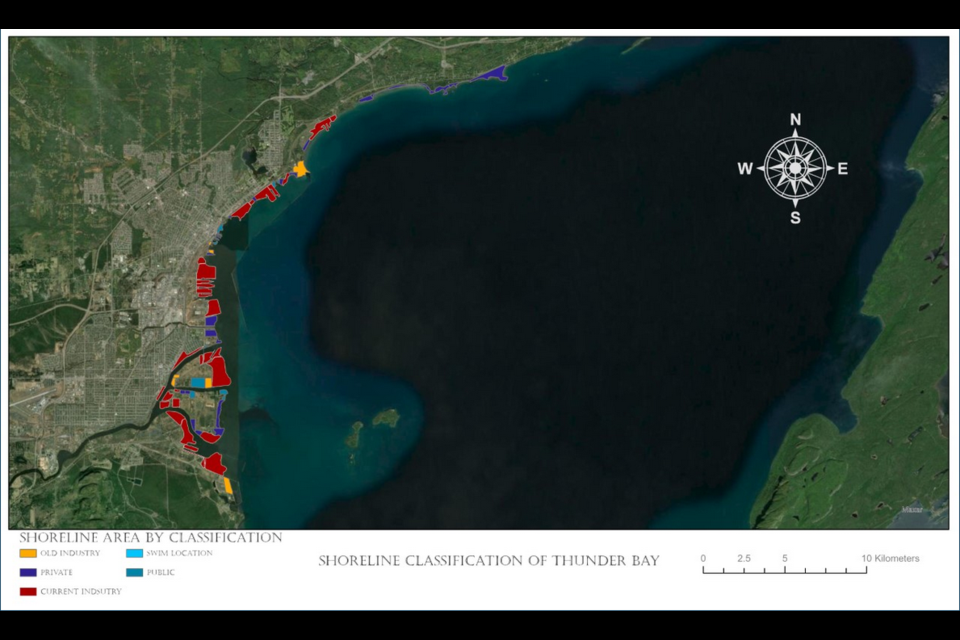

As it turns out, what it looks like is a lot of red and yellow — representing current and former industry, respectively, on the map the pair created — with just a few small patches of light blue, representing public access and swimming areas.

That map and a project description are available online.

The results of the mapping project suggest 65 per cent of the city’s shoreline is taken up by current industry, eight per cent by former industry, 21 per cent is privately owned, and six per cent is available for public access.

It also indicated there are nearly no places where it’s safe to access swimming along the city’s shoreline.

The project covered the area of shoreline running roughly from Fort William First Nation in the south up to Black Bay in the north.

The pair note the study is not exhaustive and some data may not be completely up to date, so the results give a general sense, rather than precise statistic, of shoreline usage.

Greenberg said the results are sobering, but not surprising.

“I was not surprised at all,” he said. “I grew up spending a lot of time on Georgian Bay … Moving up to Thunder Bay, it was like, wow — it’s like a lake town where it’s really hard for anyone to get out onto the lake, in a way.”

While residents likewise may not be surprised by the numbers, the pair hope seeing them laid out and visualized will inspire further conversation about the city’s waterfront.

“When you put it in a map, for some people that’s a good way, or when you break it down into a pie chart, that can make it sink in for people,” he said. “Us being able to share it afterwards and getting some conversations going was definitely a bonus to the project.”

Dyck pointed to encouraging recent signs of a push for more activity and access on the waterfront.

“I think the talks around us getting a Science North building down on the shoreline, and even the art gallery, they’re having to rehabilitate shoreline for that,” she said. “So the government’s putting money forward to encourage that, which is a start.”